Clinical Frailty Scale

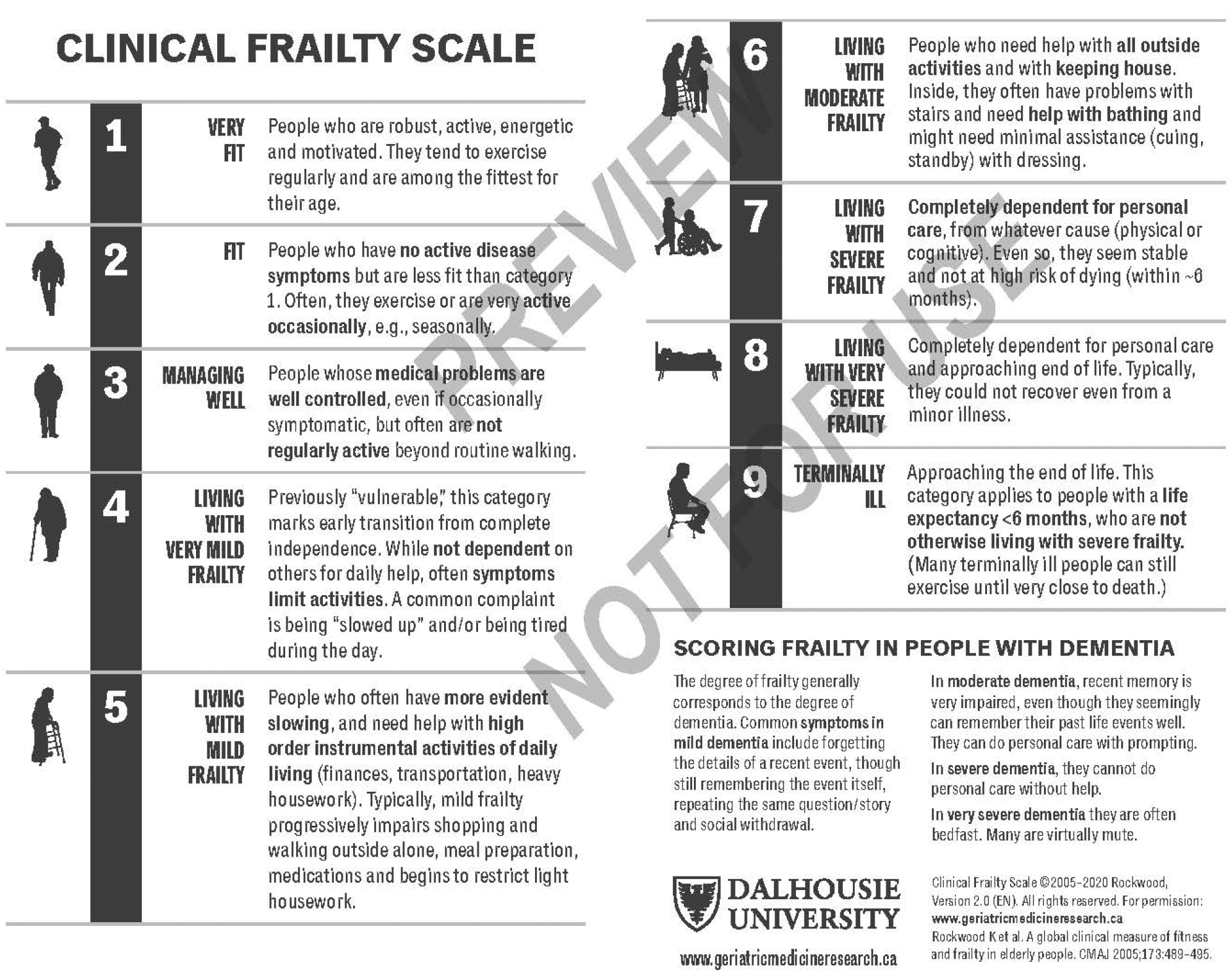

The Clinical Frailty Scale (CFS) was introduced in the second clinical examination of the Canadian Study of Health and Aging (CSHA) as a way to summarize the overall level of fitness or frailty of an older adult after they had been evaluated by an experienced clinician (Rockwood et al., 2005).

Although introduced as a means of summarizing a multidimensional assessment in an epidemiological setting, the CFS quickly evolved for clinical use, and has been widely taken up as a judgement-based tool to screen for frailty and to broadly stratify degrees of fitness and frailty. It is not a questionnaire, but a way to summarize information from a clinical encounter with an older person, in a context in which it is useful to screen for and roughly quantify an individual’s overall health status.

The highest grade of the CFS (level 7) as published in 2005, incorporated both severe frailty and terminal illness. Later, it became evident that we needed to distinguish between identifiable groups who were otherwise lumped together in the original scale – severely frail, very severely frail and terminally ill - as clinically distinct groups who required distinctive care plans. Therefore, in 2007 the CFS was expanded from a 7-point scale to the present 9-point scale, and it has been used extensively in that format. We published on the predictive validity of the 9-point CFS in 2020 (Pulok et al., 2020).��

In 2020 the CFS was further revised (version 2.0) with minor clarifying edits to the level descriptions and their corresponding labels. Most notably, CFS level 2 changed from "Well" to "Fit", level 4 from "Vulnerable" to "Living with Very Mild Frailty", and levels 5-8 were restated as "Living with..." mild, moderate, severe, and very severe frailty, respectively (Rockwood & Theou, 2020).��

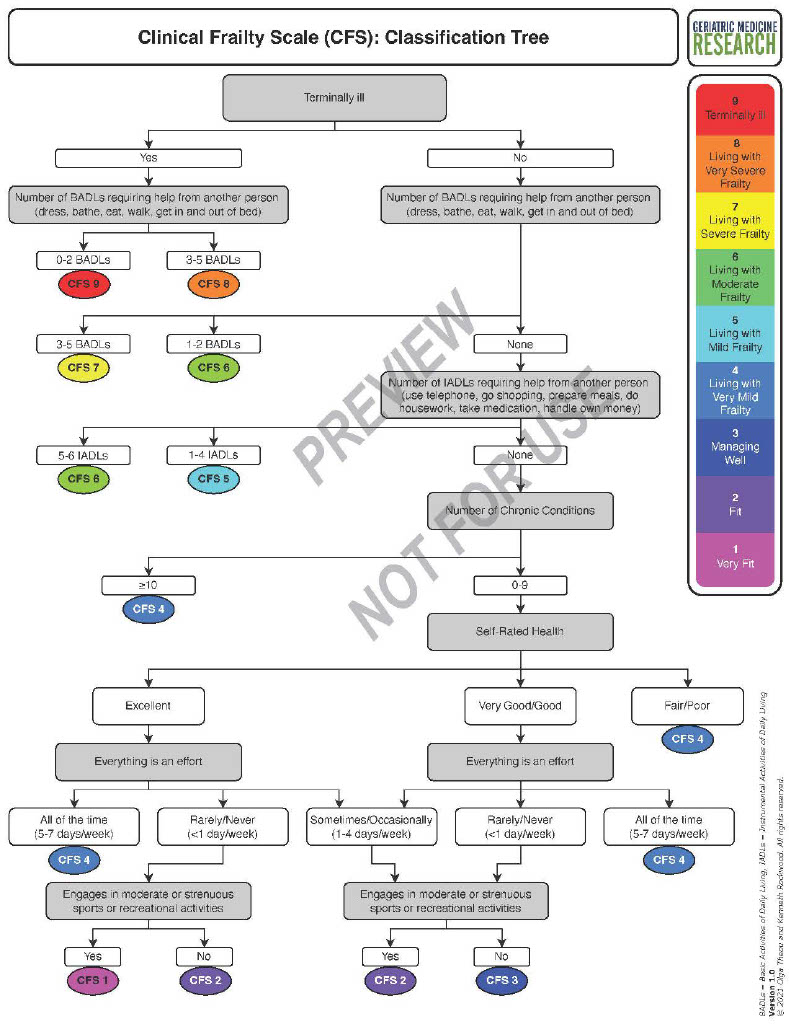

Please refer to the��CFS Guidance and Training��section below for more information and resources about using the Clinical Frailty Scale. We've also developed a��classification tree��to assist novice raters with CFS scoring:

��

CFS Classification Tree

Scoring the Clinical Frailty Scale (CFS) requires clinical judgment. Increased uptake of the CFS internationally – bolstered by the recent COVID-19 pandemic – has led to the CFS being used by many health care professionals who do not have formal training in frailty care. While the CFS generally has very good inter-rater reliability, CFS scoring by inexperienced raters may not reflect expert judgment. We developed a classification tree��to simplify��use of��the Clinical Frailty Scale for novice raters.��

This classification tree is not intended to replace the CFS��or clinical judgement. It may not be useful to experienced CFS raters, but it can aid��in routine CFS scoring for inexperienced raters. Even so, raters using the classification tree should confirm whether their clinical judgement agrees with��the CFS score derived by��the classification tree. If the rater does not agree with the��CFS level proposed for their patient by the��classification tree, they should use clinical judgement to determine the appropriate CFS level. In��a prospective study of 115 older adults assessed in an emergency department, the level of frailty derived using the classification tree matched the CFS��score assigned by an experienced geriatrician in 63% of the cases; an additional 30% agreed within +/- one level��(Theou��et al., 2021).

The CFS classification tree can be��navigated��using routinely collected clinical data. If routine��data are not available, raters can use a questionnaire��we��developed to collect the data��needed��to navigate��the classification tree��and arrive at a CFS score.��The����[PDF - 540KB] allows raters to��record��information��about specific��health conditions.��There is also a ��[PDF - 77KB] of the questionnaire��that��captures information about health conditions in aggregate��(e.g. the total number of��health��conditions).��Both versions assess��the same health domains.

In addition to the paper form, the questionnaire (in its full and short versions) can be accessed as an����with the classification tree algorithm embedded. Using the online tool, users are prompted to respond to questions until the algorithm collects enough information to propose a CFS score. The online tool does not save or store data.

As a result of its worldwide uptake, the Clinical Frailty Scale is now available in a number of languages (see��Translations).��

��

Training and Guidance

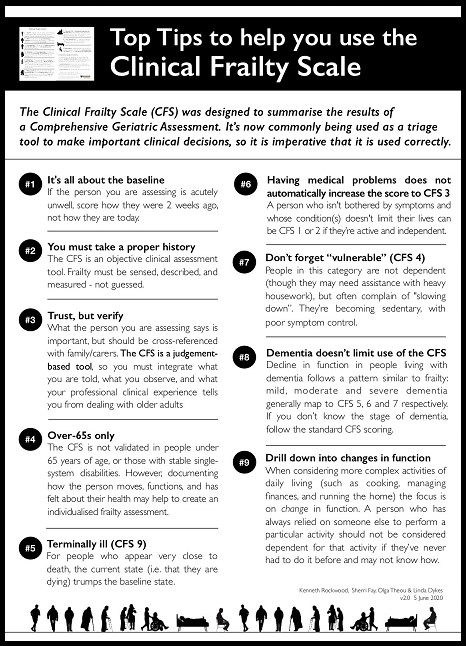

Guidance for using the��Clinical Frailty Scale��has been published in��.

Partnering with��, we developed the "Top Tips to help you use the Clinical Frailty Scale" as a resource for new or novice users of the CFS (see download links below image):

��[PDF - 508 KB]

��[PDF - 507 KB]

��[PDF - 530 KB]

��[PDF -533 KB]

��[PDF - 529 KB]

��[PDF - 529 KB]

��[PDF - 540 KB]

��[PDF - 540 KB]

��

Additional Resources

��

References

Rockwood K, Song X, MacKnight C, Bergman H, Hogan DB, McDowell I, Mitnitski A.����CMAJ.2005;173(5):489-495.

Pulok MH, Theou O, van der Valk AM, Rockwood K.��.��Age Ageing.��2020;49(6):1071-1079. ��

Rockwood K, Theou O.��.��Can Geriatr J. 2020:23(3):210-215.

Theou O, Pérez-Zepeda MU, van der Valk AM, Searle SD, Howlett SE, Rockwood K.��Age Ageing. 2021;50:1406-1411.

��

Permission for Use

To guard against copyright infringement or unlicensed commercial use, we ask all potential users to complete a��Permission for Use Agreement via the��online��Permission Request Portal.��Agreements are reviewed by the Industry Liaison Office at ��ɫ�� to determine whether a license agreement is required. Requests for non-commercial educational, clinical and research use, as well as for reprint usually do not require a license agreement.